A Small Question with Big Implications

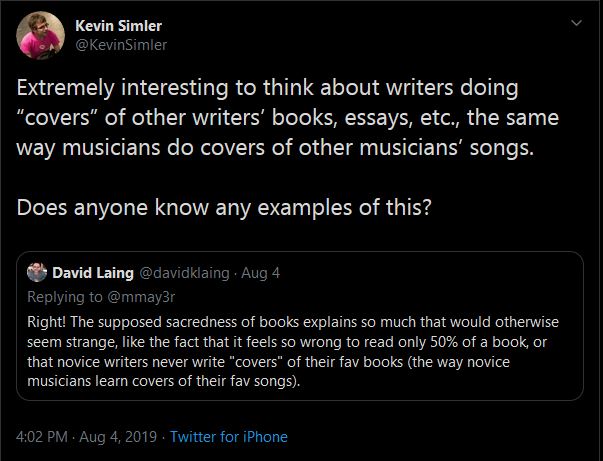

Last month, I stumbled upon a tweet that got me thinking. It was from Kevin Simler whose main background is in computers, language, and philosophy. He has a provocative blog, Melting Asphalt, where he posts sporadically, but all his essays are interesting to read. (Warning: they will make you think.) His tweet that inspired this article was an expansion on the thought of another person, David Laing, who I’d like to say something nice about, but I have no idea who he is.

Let’s break down the original tweet from Laing into its main propositions.

Let’s break down the original tweet from Laing into its main propositions.

1. Observation — musicians cover other songs

2. Observation — writers don’t “cover” other books

3. Explanation — books are considered sacred, implying it would be wrong to create cover versions

As both a writer and a musician, I feel somewhat qualified to address these points. And well, to put it bluntly, Laing is simply wrong.

Before we test this sacredness hypothesis, we should first ask if Laing’s observations are true. This is the question that Simler poses, because as I said, he’s good at thinking things through. Covers of songs are obvious and common, but do we have examples of books that are “covers” of other books? The answer is also yes, but we don’t call them covers. We call them retellings. The first examples that come to mind are Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, which can be seen as a retelling of Romeo and Juliet, and Joyce’s Ulysses, which is a deliberate retelling of Homer’s The Odyssey. There are also numerous examples of fairy tales and biblical stories re-created to fit modern times. Since the observation is false, there’s no point in coming up with an explanation. This seems simple enough. But, in my characteristic way of overthinking things (and why it took a month to respond), I found another way to approach this.

As you can see, covering another artist’s work is common in both literature and music. So the question isn’t why “covers” of books don’t exist but why we think they don’t. The real issue is that literature retellings aren’t as easily recognized as such compared to music covers. I started wondering why that is. And this is where we start to turn down a more interesting path. To understand this lack of recognition, we need to understand the nature of music and writing and the inherent differences between the two art forms.

How and Why We See “Covers”

Let’s first address the purpose of creating covers. There’s an underlying assumption in Laing’s tweet that covering another work of art is primarily a learning mechanism. He doesn’t directly state this, but it’s implied when he mentions that covers are something to be undertaken by both “novice” writers and musicians. It is true that copying another artist’s work can be a way to learn the craft. But this is true for both music and writing. So, stating that “novice writers never write ‘covers’ of their favorite books” as a method of practice is simply wrong. One assignment in college I specifically remember was copying We Real Cool by Gwendolyn Brooks. I had to copy the rhythm exactly to learn how it affects not only the feel but also the meaning of a poem. Add in all the sonnets and villanelles I had to practice, all usually derived from the works of other famous writers of these forms, and you can see that writers do indeed copy the masters as a way to hone their craft.

Granted, I wasn’t copying Brooks’s poem word for word, while as a musician, I would learn a song note for note. There’s a reason for that, which we’ll get to, but for now, the important thing to remember is that when an artist copies another’s work as a learning method you’ll never see it. Artists don’t release their practice work to the public. Musicians don’t get on stage and run through scales for the audience. By the same token, no one will ever see my copy of Brooks’s poem. This is because the whole point of creating art is to come up with your own work. (There is one exception to this in music, which I’ll address below.) So any covers you find must be more than practice exercises. The cover has to deviate from the original to be worthwhile for a musician to go through the trouble of releasing it. Therefore, any cover that you would actually see is a variation of the original, not an exact copy.

From this standpoint, publicly released covers need to satisfy two criteria in relation to the original:

1. Recognition — similar enough to be recognized as a cover

2. Expression — different enough to be a new expression, not simply copying or practice

The clearest way to examine the first criteria is to break down the art forms into their constituent elements and examine which change and which don’t between versions. Then we’ll explore how those changes affect our ability to recognize different versions.

To Recognize Music Covers, Melody Must Stay Same

We’ll start with music. (Note: the following is a bit oversimplified, but I’m trying to not get too detailed into music theory here. I’m just going to ask you to trust the musician about music.) The most commonly and simplistically stated elements that make up music are rhythm and melody. But songs are also made up of a chord progression, time signature, key, arrangement (instrumentation), and tempo. All of these work in conjunction to turn sounds into a song. Now if you examine covers, you’ll see that only one element is required to stay consistent between versions to make them recognizable as covers — the melody. To demonstrate this, pick a song, any song. Now hum or whistle that song. You’ll hum the melody line. If anyone hears you, they’ll also recognize the song, assuming they’re familiar with it and you can hum in tune.

All other musical elements either define or support the melody, or they simply function to keep all the parts together. Definitional elements consist of the chord progression and time signature. This means they must also stay the same between versions but only to keep the melody consistent. It would be impossible to change these without changing the melody. Rhythm is the main supportive element. This gets a little tricky as technically every part (melody, harmony, etc.) has a rhythm. For our purposes, I’m including the melody rhythm and the rhythm of the chord progression with their respective elements. So when I refer to rhythm from here on out, I mean the overall song rhythm underlying the melody, which is usually established by percussion and bass instruments.

Because rhythm plays a supportive role to the melody, there is much leeway in changing it around, and as our humming illustration above demonstrates, it can even be dropped entirely. However, because each part’s rhythm has to coincide to some degree, certain accented beats need to stay the same between versions. But outside of these specific rhythmic moments, you can pretty much do what you want as long as you stay with the time signature.

Key and tempo mainly function to keep all parts playing together. So it’s true that if these change, everything else changes, but these changes don’t affect the overall recognition of a song in any way. Changes in arrangement are pretty easy to see as having no effect on song recognition, whether it’s played on a piano, guitar, kazoo or anything else.

Overall, the melody defines any song from a recognition standpoint. This makes the melody a quasi-independent element, so it must stay consistent. The other elements can change, but due to their supportive nature, they are somewhat limited in their variability. If they change too much, it’s not that the melody will be unrecognizable, it’ll just sound like shit. To see this in real life, let’s listen to a few musical versions of the song, Hurt.

Hurt, Nine Inch Nails (original)

Hurt, Johnny Cash (cover — with vocals)

Hurt, 2 Cellos (cover — instrumental)

Through the three versions, you’ll hear how the melody (and therefore time signature and chord progression) remains consistent, while everything else varies. Even when the melody goes from being delivered via vocals to a cello, the melody line itself remains the same. It’s all the other elements that change, some more than others. All three versions are in different keys and played at different tempos. But if you weren’t listening to these side-by-side or not specifically paying attention to it, you’d never notice. The most drastic changes are in arrangement and rhythm, with the latter somewhat necessitated by the former.

Overall we have two distinct rhythms in this song. The verse rhythm revolves around arpeggios (chords where the notes are played individually instead of together) that flow then hold. The sustained notes hold on the second beat of every other measure. In the pre-choruses and choruses we have pulsing quarter notes. Now these general rhythms remain consistent between versions, mainly because they keep the melody sounding “right.” But if you listen closely, the way these rhythms are created is quite distinct between versions.

In the NIN verse, the arpeggios, played only by a guitar, use more tied notes and add additional passing notes to give a more meandering and complicated rhythm. In Cash’s version, again on guitar, the arpeggios are more regular, which produces a more flowing and less disjointed feel. In the 2 Cellos version, the arpeggios are stripped to their bare essentials with no passing notes and the most regular feel. Combined with the low sustain of a cello, when plucked, this rhythm creates the most space and airy feel of the three. In the NIN pre-chorus, a guitar and bass play only quarter notes, and as we move into the chorus, the guitar drops out, and the bass and added drums play eighth notes that are still accented on every beat, continuing the established quarter note dominant rhythm. In Cash’s chorus however, the guitar begins playing a mix of quarter notes and eighth notes and uses added piano to keep a quarter note accent. Again this makes the overall rhythm less choppy. There are no additional rhythmic notes in the 2 Cellos chorus — it’s all quarter notes and nothing else.

As you can hear, these rhythmic and arrangement differences effect the feel of the song but not our ability to recognize each as different versions of the same song. We’re still left with the melody, which defines any song from a recognition standpoint, as the only truly consistent element.

In Literature Retellings, Everything Changes

Now let’s break down literature into its constituent elements and examine how they affect our recognition of retellings. We have a narrator/point of view (POV), characters, a setting, a narrative/plot, and themes. Unfortunately it’s not quite as simple as pointing out which of these elements must be kept between retellings. As we’ll see, all of them usually do change between retellings.

Take A Farewell to Arms as a retelling of Romeo and Juliet, as mentioned above. The narrator changes from third-person to first person. The characters have some similarity, but there is a bit of a gender reversal — Catherine is more similar to Romeo and Henry is closer to Juliet in many ways. The characters in the two stories also vary in personality and temperament. The two settings are similar as taking place in a conflict-ridden Italy, but the two time frames create obvious differences. The most consistency between the tales is their narrative arc — two people fall in love by chance, they begin a clandestine affair, they make plans to run off together, the plan is thwarted and they are separated by the conflict, they reunite. However, the ending is completely different. Only one of them dies, and the circumstances of her death are different, most importantly it’s not a suicide. Both stories also deal with similar themes, especially the idea of renouncing conflict to pursue love. But in A Farewell to Arms themes such as masculinity are added and others like familial obligation are dropped.

In terms of meeting the recognition criteria for covers, you can see everything is similar enough that we can call this a retelling, but nothing stays consistent either, at least not in the way melody remains consistent between song versions. This begs the question though, can’t authors simply change things less? Not really. Compared to music, not only do more elements change between retellings of literature, they must change. The reason for this gets us into satisfying the second criteria for creating a cover — new expression. And now we’re getting to the good stuff. As we dig deeper, we’ll find that changing all elements in literature but not in music is necessitated by the inherent differences between the art forms in expressive capabilities and how the audience understands those expressions. Grab a shovel.

Artistic Building Blocks and the Difference Between Music and Language

Notice that I didn’t list musical notes as a constituent element of music, nor words for literature. These are building blocks. They provide the raw material for their respective art forms. Elements are structural. To see the difference, if I simply played a random set of notes, you wouldn’t have a song. In the same way, picking random words from the dictionary wouldn’t create a work of literature. However, it is the differences between notes and words that create the inherent differences between music and literature and, in turn, their expressive capabilities.

The main fundamental difference is that music is experienced sensually while literature is not. This means we experience every aspect of a song directly and exclusively through our senses (hearing). We don’t need any additional mental processing to understand a piece of music as music. This should be self-evident. You don’t need to know anything about music theory, what key the song is in, what notes or chords are being played, etc. to enjoy a song. The sensory experience alone creates an understandable expression.

However, when we experience literature, it is expressed through language, which requires an extra level of abstract cognition to understand it. This might not be obvious because language does produce both an auditory and visual sensory experience for speech and writing, respectively. Also, this extra cognitive step is so automatic that we’re not usually consciously aware of it. So to illustrate this effect, I’m going to rewrite the first two lines of a famous poem and keep the auditory experience as close to the original as possible.

Yet fuss dough Zen, ewe sand eye

Hen duh Steven sing fizz sped route condensed duh spy

The rhythm matches the original exactly. Each word rhymes with the original. A few are homophones. Where I had to add a sound to make a different word, I tried to use softer, less noticeable consonants. Where I changed a sound to make a different word, I tried to use a similar phonetic type. Now ask yourself, does this rewrite express anything?

Compare it to the original lines. They’re from The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock by T. S. Eliot.

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

As you can see (hear?), simply re-creating a similar auditory experience in language won’t re-create the expression of the original. In fact, it destroys it.

Variations in the visual experience of language are common. You always see words in different fonts, sizes, and colors. We also have capital and lowercase letters. Changing these aspects has no effect on our understanding of what the words express. Taken together, it’s obvious that understanding an expression in language is independent of our sensory experience. So let’s try one more thing. If I rewrite the lines to maintain a similar meaning and ignore the sensory experience, we should get something that is recognizable to the original.

Ok, you come with me

As this night stretches on endlessly

The reason that maintaining the sensory experience also maintains the psychological effect (expression) in music but not in literature is due to the different natures of notes and words. The building blocks of music, notes, do not have meaning. Notes don’t refer to anything else. They simply are. Middle C is middle C and nothing else. Creating an organized collection of notes (a song) doesn’t change this. Contrastingly, the building blocks of literature, words, do have meaning in and of themselves. They are symbols that refer to something else, namely conceptions of things in the world. So to understand a word, you have to know what the word refers to and this is independent of the sensory experience of the word. And this fundamental difference between notes and words gives us our fundamental differences between their two respective art forms. Listening to music is experiential, while reading literature is cognitive.

Music Expresses Emotions, Literature Expresses Ideas

This difference between art forms has profound implications. Most importantly, it creates necessary expressive limitations unique to each art form. All expression basically boils down to two types: ideas and emotions. Emotions do not require a level of abstract cognition. It requires cognition to name the emotion, to say “I feel sad” or “I feel happy”. But it doesn’t require cognition to actually feel those emotions. You simply feel them.

Ideas are made up of multiple concepts associated together, influencing each other. The way concepts influence each other is what we call context. Context is essentially the prior knowledge and assumptions of the audience when confronting a new concept. Change the context and you change the understanding of the new concept, which ultimately shapes how an idea is understood. This means that both expressing and understanding an idea require additional cognitive processing versus feeling an emotion.

Now let’s apply this analysis of expression types to music and literature. As highlighted above, musical expression is delivered purely through sensory experience. And just like emotions, you don’t need cognition for sensory experience. If you heard a trumpet playing a note, you would need cognition to understand that the note is being played by a trumpet. But if you had no concept of trumpets, you would still hear the same note, and it would be bright and loud and the same pitch. Since musical expression is delivered and understood strictly through non-cognitive means, music cannot express ideas. An easy way to demonstrate this would be to try explaining the theory of relativity or how to fix a car through music. All that’s left for music is non-cognitive expression. In other words, music can only express emotions.

As shown above, words can only express concepts due to their referential nature. And when you collect the words in different combinations, the meanings can change individually (but not always), but also add up to a larger meaning for the work itself. This is the effect of context. The interplay between theses individual meanings creates the aggregate meaning or idea, which requires cognition to understand. Therefore, literature primarily expresses ideas.

Now it’s true that literature can also express emotion, but it’s not expressed the same way as music. Any emotional expression is indirect. It’s derivative from the expressed ideas. To see this, notice how it’s possible to create expressions via language that are absent of emotional content, i.e. legal documents, instruction manuals, etc. It’s not possible to create a song that doesn’t have an emotional effect. (If you can think of an example, I’d love to hear it.)

So in a nutshell, we have a model of how both art forms are built and how they operate on the audience. Both art forms use their individual building blocks to create an expressive work. The work creates a sensory experience in the audience. Both art forms ultimately create a psychological effect in the audience. With music, this effect stems directly from the sensory experience, which also limits the effect to an emotional understanding. In literature there is an added interpretive step to create the psychological effect, which limits the immediate effect to understanding ideas. Any emotional effect becomes secondary.

Musical work → sensory experience → psychological effect (emotion)

Literary work → sensory experience → symbolic interpretation → psychological effect (idea) → psychological effect (optional emotion)

Finally — Why Literature Retellings Are Hard to Recognize

Now we can address the original issue that got us to this point. With our understanding of the differences between art forms, we can truly see why literature retellings are harder to recognize than music covers. Our ability to recognize two things as similar or the same is largely based off our sensory experience. We tend to think things that look alike or sound alike are alike.

In music the sensory experience drives both recognition and expression. In other words, the sensory experience has a larger overall impact. In terms of the recognition criteria, if a musician deviates too much from the original, especially the melody, the song will be thought of as a different song. However because the expression is also driven by the sensory experience, a musician can create new expressions with smaller changes. The result — new expressions that maintain a high amount of similarity to the original song and are therefore easy to recognize as covers.

And since the musical expression is sensory driven, that expression is limited to emotion. So these changes to non-melodic elements should create different emotions, but within a narrow range. Our examples of Hurt above confirm this. The expressive differences between each version all fall into the emotional range of sadness. However, in the original we get more of an unraveling, desperate despair. In the Cash version, it’s more of a broken regret. And in the 2CELLOS version, the song expresses more of a quietly endured grief.

In literature, the sensory experience only drives recognition. Expression is independent. Here the sensory experience has a small overall impact. So to satisfy the expression criteria, the retelling needs to deviate from the original, and due to how ideas are constructed, changing one element necessitates changing others to keep the new expression coherent. In other words, context matters much more in literature than it does in music, and providing a new take on an idea requires changing the context. Since context is an amalgam of prior concepts, that means every element of a story can, and usually does need to, be changed. Narrative and narrator determines what information the reader knows and when. Different settings limit the available actions of characters, i.e. you can’t have someone taking pilot lessons if the story is set in the 19th century. Characterization influences our understanding because we recognize in both real life and stories that the words and actions of different people have different meanings (think of a character saying “I can do this,” — it means something different if the character is a young boy stepping up to bat in the big game or a suicidal man standing on the ledge of a building). This results in a larger degree of change in the sensory experience, which makes a literature retelling harder to recognize.

Because literature is cognitive, it means the identification of a retelling isn’t based on the sensory experience. Instead a retelling is based on how the respective works explore similar ideas via using similar, but variant, elements. Going back to our Farewell/Romeo and Juliet comparison, we can see this in action. The reason the stories, while similar, diverge so much is because Shakespeare and Hemingway were saying different things about the same topic. Simply switching from third person to first person necessarily effects the plot as only actions by the narrator or witnessed by the narrator can be related. Information gets dropped, i.e. the audience can’t know what’s going on with Catherine while she’s separated from Henry. This in turn refocuses the conflict on to the challenges faced by Henry. This explains some of the thematic variation, especially why themes like familial obligation disappear, as this theme was mostly represented in Romeo and Juliet through the plot elements revolving around Juliet. More conscious narrative changes, especially the deaths at the end, also affect the approach when dealing with similar themes. While both stories deal with love, their statements about love differ. In Romeo and Juliet, love is all consuming. The characters go to extreme measures to be together. When it turns out that they still can’t, love finally consumes them both as they take their own lives. In Farewell, Catherine dies a natural death. Henry lives on. In this case love is not all consuming but just one more way that life can turn to shit. The point is to keep going anyway. So in the latter story, the theme of love is used to elucidate another larger theme — the need to endure the hardships of life.

The Exception and Last Difference Between Music and Literature

So far, everything we’ve discussed has been premised on the idea that the purpose of an artist covering another work is not to recreate the original artwork exactly, but to offer a different take or expand on the original. But as I mentioned earlier, there are cases where covers are not new artistic expressions, but they are publicly released, so they’re not a learning tool either. Historically, this has only applied to music. It’s the phenomenon of the tribute band where the goal is to reproduce the original exactly. Classical music performances also generally fall into this category. Now the question is why do we see attempts at exact reproduction in music and not literature?

This gets us into the last fundamental difference between the art forms. Music is performative while literature is not. But this is also due to the differences in how the two are experienced and understood. It’s a production issue, really. Because musical expression stems directly from the sensory experience, producing music (the actual sounds) requires performance. The musicians need to be there, playing. Yes they could record their work, but if their goal is exact reproduction, what’s the point between their recording and the original? A recording in this case serves more as a money-making, marketing vehicle, not an artistic one. And this is why you see tribute bands and classical ensembles heavily emphasize live performances. Another commonality is that they are mainly covering musicians who no longer perform, either because the original musicians are dead or no longer practicing publicly. What tribute bands are doing is creating musical performances that are no longer available from the original artists.

Since literary expression is cognitive, the sensory experience is less important. Therefore performance is a non-factor. Think about what it would mean to witness a live performance of a writer reproducing a literary work exactly. You would be reading over his shoulder while he types out someone else’s words. The actual idea presented would still be the exact same as reading the original. And since you can always by a copy of the original work, there’s no value to a writer in exactly reproducing an original. About the closest we come to performance in literature is live readings and audio books. But even then, if the performance is done by someone other than the author, we don’t think of it as a retelling. You can see this in the difference in attribution. In our cover song examples, we attribute the Johnny Cash version to Cash, not Nine Inch Nails. But when you “read” an audio book, we still attribute the work to the original author. Basically, the ideas expressed in literature remain in the work itself. The writer doesn’t need to be present producing the text as you read it. Therefore, performance is not applicable.

Bringing It All Together

To sum everything up, Laing’s observation that writers don’t “cover” other works of literature the way musicians cover other songs is false. Writers do “cover” other works. This makes any explanation irrelevant. However, explaining this misconception allows us to better understand the fundamental nature of music and literature and how they differ. At the root of it all, musical expression is built by notes whose understanding is derived solely from sensory experience, while literary expression is built by words whose understanding is derived from symbolic abstraction. This creates all the other differences we see. Music is experiential, limited to emotional expression, and performative. Literature is cognitive, limited to expressing ideas (emotional expression is derivative), and non-performative.

These inherent differences between the art forms produce the misperceptions of Laing and Simler. From a cover-as-new-expression standpoint, smaller changes in music are enough to create an expressive difference between versions. This creates higher similarity between versions on a sensory level, so they’re more easily recognizable as covers. Contrastingly, larger changes are required in literature to create an expressive difference between versions. This creates more variation on a sensory level, so they’re harder to recognize as covers.

From a cover-as-exact-reproduction standpoint, this only has value in performative situations, which largely only apply to music. It could be that Laing meant this second way of looking at covers, in which case, it is mostly true that we don’t see literary “covers.” However, his thought of covers being produced by “novices,” implying that covers are learning tools, undercuts this benefit of the doubt. The musicians in tribute bands and classical ensembles are certainly not novices. But even if Laing was only referring to covers in this second sense, the reason for the lack of literary covers is still best explained by the non-performative nature of writing, which is also predicated on its cognitive nature. So no matter what, and as much as I’d like it to be true as a writer, any supposed sacredness of books has nothing to do with anything regarding covers.